UPCの最初の判決が下された。クレーム解釈、事実の開示と立証の責任、さらに進歩性の検討など、多くの議論がなされている問題に関するUPCの立場を知ることは、エキサイティングなことである。

1. クレーム解釈-序論およびEPOとの比較

EPOでの手続では、クレーム解釈において明細書をどの程度考慮すべきか、また(存在するなら)その法的根拠、についての議論が続いている。

審決T 1473/19において、審判部(BoA)は、EPC第69条とその解釈に関する議定書第1条が、審査手続及び異議申立手続の両方において、クレームの解釈及びクレーム範囲の決定に関して依拠することができるという結論に達した。また、EPC第69条第2項によれば、クレームの解釈には明細書及び図面を使用しなければならないとあるが、依然として、クレームの特徴を解釈する際の制約を設ける、クレーム優位性が存在する(EPC第69条第1項によれば、欧州特許または特許出願によりカバーされる保護範囲はクレームによって決定される)。

さらに、クレームがそれ自体で明確であっても、クレームをさらに解釈するために明細書をさらに参照することができると判決された。

しかしながら、「クレーム優位性」の原則により、クレームの特徴の解釈では、曖昧でない(明確な)クレームの文言が明細書よりも優先されなければならないため、クレームの解釈のために明細書を参照することは、結局のところ、曖昧なクレームの特徴についてのみ可能である。

T 0169/20において、審判部は、EPC第84条の条文、特にその第2項、およびEPC規則第42条および第43条が、特許性を評価する際のクレーム解釈について適切な法的根拠を提供すると結論付けた。EPC第69条は、(前述のT 1473/19に反して)EPC第123条(3)への適合性を審査する目的で保護範囲を決定するため、そして侵害訴訟手続においてのみ使用された。審判部はさらに、「クレームの文言がそれ自体明確で技術的に合理的であれば、明細書に照らして解釈することは必要でも正当化されるものでもない。特に、関連する技術的文脈の中で合理的かつ技術的に妥当な解釈を除外するなど、クレームの文言を読んだ当業者が理解するであろう思われる範囲を超えて発明の主題を制限又は変更するために明細書の記述を利用すべきではない」と結論づけた(下線は追加)。

要約すると、EPO審判部の両例示審決は、異なる法的根拠(EPC第69条とその議定書第1条の組み合わせ、あるいはEPC第84条とEPC規則第42条、第43条の組み合わせ)を適用しているが、クレームの主題を定義するのはクレームの文言であり、明細書は曖昧な特徴を解釈するためにのみ使用することができる、という同様の結論に至っている。

さて、UPCの最初の判決が下りた現在、クレーム解釈に関するUPCの立場を注目してみよう:

統一特許裁判所(UPC)の控訴裁判所(CoA)は、判決UPC_CoA_335/2023 (修正済み) において、「特許クレームは、EPC第69条とEPC第69条の解釈に関する議定書に基づいて欧州特許の保護範囲を決定するための出発点であるだけでなく、決定的な基礎である」と決定した(頭注2、第1項)。さらに、UPCのCoAは、「明細書と図面は常に、特許クレームの解釈のための説明の補助として使用されなければならず、特許クレームの曖昧さを解決するためだけに使用されるものではない」という驚くべき結論に達した。(強調部分は追加、命令理由5.d) aa) 第3段落)。これは、クレーム解釈のために明細書を参照することは、クレームの特徴が曖昧な場合にのみ可能であるとしたEPOの審判部の立場とは異なる。UPCの控訴裁判所はさらに、クレーム解釈の目的は「特許権者の適切な保護と第三者の十分な法的確実性を両立させること」であると述べている。(命令理由, 5.d) aa) 第6段落)。

判決UPC_CoA_335/2023において、控訴裁判所は請求項1の特徴の一部、例えば「細胞又は組織サンプル」、について解釈が必要であるとした。この点は、裁判手続きにおいて実際に問題となった。というのは、この特徴を解釈すること、特に、細胞または組織から抽出され支持体に結合されたサンプルはクレームの「細胞または組織サンプル」であると考えられるか?ということが、実質的な特許性を評価する上で重要であったからである。控訴裁判所によれば、この特徴は、細胞または組織のサンプルが依然として細胞または組織として認識可能なサンプルとして理解されなければならないと要求している。さらに控訴裁判所は、この理解を支持する明細書も参照した。

結論として、UPCの控訴裁判所は、EPC第69条と第69条の解釈に関する議定書に基づき、クレームの特徴が曖昧な場合だけでなく、クレームの解釈のために明細書を常に考慮しなければならないという立場をとっている。

2. 仮処分における事実の開示と立証の責任

手続規則第205条及びそれ以下に基づき、仮処分命令は略式手続(一般に仮処分(PI)手続とも呼ばれる)によって出されるが、この略式手続では、当事者が事実や証拠を開示する機会が限られている。

これまで、仮処分手続に関する国内法および実務は、欧州諸国間でかなり異なっており、ドイツの実務でさえ、統一されたアプローチはなかった 。

控訴裁判所によれば、一方では、遅延によって特許権者に回復不能な損害が生じるのを避けるため、立証基準を高く設定しすぎてはならないが、他方では、後日取り消されることとなる仮処分命令によって被告が損害を受けるのを防ぐため、低く設定しすぎてもならない。

手続規則第211.2条によれば、出願人は、「出願人が第47条に基づき手続を開始する権利を有すること、当該特許が有効でありその権利が侵害されていること、またはそのような侵害が差し迫っていることについて、十分な確実性をもって裁判所を納得させる合理的な証拠を提出することを要求される」場合がある。

控訴裁判所は現在、このような「十分な確実性の程度は、裁判所が、出願人が手続を開始する権利を有し、特許が侵害されている可能性が少なくともないよりはあると考えることを必要とする。裁判所が蓋然性の均衡において特許が有効でない可能性がないよりはあると考えている場合に、十分な確実性の程度が欠けている」と判示している(命令理由、5. a) 第4段落)。

つまり、UPCの控訴裁判所は、「蓋然性の均衡」評価を裁定した。特許が無効である可能性がないよりはある場合、仮処分手続は不成立となる。この概念は、特許が新規性または進歩性を有しないと判断される可能性が高いかどうかという「単純な」質問に帰結する。この場合、UPC裁判所は特許侵害訴訟において仮処分手続を認めない。

つまり、この判決は、各国裁判所の間で対立する様々な判決とは異なる、UPCの下での共通基準を提供するものである。

3. UPCにおける進歩性の検討

UPC_CoA_335/2023では、控訴裁判所は、請求項1の主題が自明であると証明される可能性はそうでない可能性よりも高いという結論に達した。興味深いことに、控訴裁判所はこの判決により、この部分に関する第一審裁判所による反対の認定を覆した。

控訴裁判所は、関連する先行技術文献D6と請求項1との唯一の相違点は、請求項1の方法が細胞または組織サンプル中の複数の分析物を検出することを意図しているという特徴をD6が開示していないとの認定に基づいて結論を下した。むしろ、控訴裁判所は、D6は「増幅DNA分子」(ASM)を検出することを意図した方法を開示しており、これらの分子は細胞または組織サンプル中には存在せず、当業者には該特許の意味における細胞または組織サンプルとは見なされないであろう、と考えた。このため、新規性が認められた。

控訴裁判所はさらに、進歩性について、試料中の標的分子を検出するための高スループット光多重法を開発しようとする当業者であれば、複数のASMを検出する方法を開示しているD6を考慮したであろう、と述べた。この文献から出発して、優先日当時、多重分析技術に対する需要があったことを念頭に置けば、当業者であれば、さらなる文献(B30)によって証明されているように、D6の方法をin situ環境に移すことも検討したであろう。驚くべきことに、困難に直面した当業者が成功の見込みが不十分であるために試験を行なわないということはなかったであろうという理由の中で、控訴裁判所はスウェーデン知的財産庁のコンサルティング報告書(B10、5頁)に言及している。

控訴裁判所は、本件特許が進歩性の欠如により本案訴訟で無効と証明される可能性は低いよりも高いと結論づけ、仮処分を出す十分な根拠はないと判断した。

弊所からのメッセージ

[1] GRUR 2022, 811 – Phoenix Contact/Harting

ミュンヘン地方裁判所:

2022年9月29日の判決, Az. 7 O 4716/22; および2022年10月27日の判決, Az. 7 O 10295/22:

欧州特許および欧州特許のドイツ特許部分は、付与公告日から有効と推定される。

デュッセルドルフ地方裁判所:

2022年9月22日の判決, Az. 4 b O 54/22:

欧州特許とそのドイツ特許の有効性の推定に疑問

[2] ドイツ最高裁, BGH – Fulvestrant (X ZR 59/17; Headnotes)

The detailed article is published at JUVE Patent.

Since the introduction of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in June 2023, a new system for central attacking the validity of and thereby to nullify a European Patent has been introduced. If a European patent of concern is an EU Unitary Patent, or if a classically validated European patent was not opted out from the competence of the UPC, a central revocation action under the UPC now exists in parallel to an opposition before the European Patent Office (EPO). Therefore, the question arises: what are the pros and cons of challenging the validity either before the EPO or before the UPC? The present report provides some guidance and discusses the main advantages and disadvantages of each system – which eventually is a matter of strategic considerations whether and which advantage may prevail – be it costs, timing, speed of proceedings, and possibly other issues.

We are delighted to announce that our managing partner Dr. Dorothea Hofer has obtained the European Patent Litigation Certificate issued by the University of Maastricht in cooperation with the Academy of European Law (ERA) in Trier. This includes an extensive practical and theoretical training in the law underlying the Unified Patent Court (#UPC) and related fields of European law so that she is well prepared for representing clients in all proceedings before the Unified Patent Court.

(III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

Opposition proceedings before the European Patent Office (EPO) are an attractive forum for challenging patents; the procedure is virtually unrivaled worldwide in terms of value for money. The process is simple, streamlined and relatively inexpensive. The practice is well tested. However, there are restrictions and drawbacks – for example, a deadline of nine months after the grant date for submission, the long duration of the opposition and appeal proceedings, and strict rules for admitting evidence submitted late.

The UPC now offers a second chance by providing another forum for central revocation of a European patent throughout the territory of the UPC states. Moreover, revocation actions can be brought before the UPC at any time after grant, independently of opposition proceedings before the EPO. Therefore, it is indeed a (further) effective attack on the European patent, and even in case European opposition and appeal proceedings were already pending in parallel. In the German legal system, on the other hand, there is the restriction – besides the fact that it only acts against the German part of the European patent – that revocation proceedings are inadmissible as long as European opposition and appeal proceedings are still pending.

The opposition procedure at the EPO is essentially a written procedure with an oral hearing at the end; the oral hearing takes place before a three-member panel and may last a full day. The UPC follows a similar approach – a written procedure followed by an oral hearing. However, there is a tight timing in the invalidity proceedings before the UPC. The UPC requires the patent owner to file a response within two months (while the EPO sets a four-month deadline); then the plaintiff may file a reply to the response within two months, and the defendant (patent owner) may file a rejoinder to the reply within one month, limited to the points raised in the reply.

The faster procedure before the UPC may allow for tactics on the nullity plaintiff’s side that weren’t available before. This is because, whilst the plaintiff can prepare his facts and arguments (and potential counter-arguments) well in advance of lodging the action, pressure is put on the defendant (patent owner) with respect to time and effort. Therefore, an efficient interaction of the patent owner with his team of attorneys is important. If on the other hand the patent owner starts with an infringement action, pressure will rather lie on the side of the infringement defendant in case he seeks to raise a defence by counter-action of nullity; this is because the counter-action should then be lodged soon after the start of the infringement action for being considered during the infringement proceedings.

A difference is that filing an invalidity action at the UPC is more expensive than filing an opposition at the EPO: court fee amounts to 20 000 EURO, whereas at the EPO it is presently only 880 EURO. The costs at the UPC are comparable to filing a German nullity action – however with the difference that the decision is effective throughout the UPC territory.

Although the opposition divisions of the EPO could, in principle, order the parties to pay the costs, this very rarely happens in practice; the predominant rule is that each party bears its own costs. The UPC Rules of Procedure provide that a winning party is entitled to reimbursement of its costs insofar as these are reasonable and proportionate.

There is also a risk that matters before the UPC will become complicated if the validity of a European patent is challenged by a counterclaim to an infringement action. In opposition proceedings before the EPO, only the validity itself is examined – the EPO does not consider infringement at all.

However, there is also the possibility that the proceedings before the UPC are split into two – i.e. a bifurcated system like the one practiced in Germany – where infringement and the validity are decided separately by two different courts (the former by the Local Division, the latter by the Central Division).

While all isolated revocation actions are heard by a central chamber of the UPC, revocation counterclaims in response to infringement may instead be brought before the then competent local chamber of the UPC; however, it is at the discretion of the local chamber to refer the revocation counterclaim to the central chamber. Practice will show which principle – the one-track or the two-track procedure – will bring overall advantages before the UPC and possibly prevail in the long run.

As can be seen from this overview, there are similarities but also differences between the opposition procedure before the EPO and the nullity procedure before the UPC. Probably the most significant difference in practice is the relatively strict time regime foreseen for the proceedings before the UPC. This is especially true when the infringement and revocation counterclaims run concurrently and thus require effective and expeditious action by the parties and their representatives. However with the benefit of a decision within a short time.

Further to Part 1: (I) Introduction and Overview

Further to Part 2: (II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

(II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

During a seven-years transition phase, the jurisdiction of the future Unified Patent Court (UPC) can be declared inapplicable, by way of an opt-out request by the IP right holder, to a pending European patent application (“EP application”), to a granted European patent (“EP”), or to a supplementary protection certificate (“SPC”). This possibility was introduced to build confidence by users on the long run. If opted-out, disputes will then continue to be handled by national courts on a country-by-country basis. Once a European patent has been opted out, it is excluded from the jurisdiction of the UPC for its entire life.

Opt-outs are not possible for unitary patents.

Opt-out requests are free of official fees and can be filed by IP right owners or by representatives admitted to the UPC. To reduce costs, mass requests on the basis of lists is recommended, using software specially developed for this purpose to reduce administrative measures on the part of attorneys. It is important to ensure that the opt-out request correctly identifies all actual owners of IP rights; the owners entered in the EPO register may not currently be the correct ones. In case of doubt, it is advisable to compare the data with official registers, e.g. to detect changes or transfers of rights in the meantime. An originally undetected inaccuracy could still be objected years later in a legal dispute, and an originally invalid opt-out may lead to the undesired applicability of the UPC.

There is a time limitation for the opt-out request: if an action is received by the UPC, e.g. in the form of a revocation action, a subsequent opt-out has no effect. On the other hand, it may make sense – for example, if circumstances or strategy change, see considerations below – to make the opted-out EP patent later accessible to the UPC by withdrawing the opt-out (opt-back-in).

An opt-out for a divisional application is independent of that for the parent application.

Advantages and disadvantages of the UPC – what speaks for an opt-out, what against?

Numerous factors in general and in particular will influence the decision whether for certain patents the benefits of the UPC outweigh the disadvantages, or whether it is better to opt out.

The advantages and benefits of the UPC outweigh the disadvantages if the following objectives are pursued:

(1) A unitary decision allows enforcement in all participating (currently 17, likely more in the future) EU countries with a single infringement action. This advantage comes into play especially when acts of infringement take place in several countries. This advantage is limited when non-participating countries are involved, such as non-EU countries like the UK or Switzerland, where infringement proceedings might still have to be brought specifically. However, these adverse effects could be neutralized again, for example, if a number of UPC states are nevertheless affected or if the remaining national courts follow the UPC judgment, or if the UPC judgment favours a party settlement; due to the speedy procedure at the UPC, it can be expected that the UPC judgment will be available first.

(2) In addition to the corresponding procedural and substantive unification and simplification, the enforcement of patents in large parts of Europe is achieved at relatively lower costs. The winning party get its costs reimbursed at least partially. Some selected cost items of UPC proceedings are listed in Table 3 below.

(3) The duration of proceedings per instance is expected to be only 12-14 months from the initiation of the proceedings to the judgment.

(4) Patent owners usually get a free choice of an appropriate venue, especially if an active rather than passive/defensive strategy is pursued. It may be expected that the four German local courts of the UPC with their competence will have a high attraction especially for patent owners. The Munich based central court has received more competence: following withdrawal of the London central court, it will now decide on chemical cases, in addition to patents pertaining to the mechanical field already allocated previous.

(5) The UPC decides with the involvement of technical judges. This can and will probably help to clarify the facts, especially in the case of technically demanding patents. In line with this favourable new feature: European patent attorneys, in case of having an appropriate additional legal qualification are now admitted to represent as a single counsel at the UPC. Thus, with the additional technical competence on both the judge’s and the representative’s side, communications “at eye level” with this panel of judges can be expected – an important advantage especially in oral proceedings.

(6) The use of a uniform language, such as English as an international standard.

(7) The expected harmonization of Europe-wide dispute regulation. And thus the avoidance of poorly predictable, country-specific case law in national courts.

(8) Effective evidence-gathering procedures, such as inspections, are possible that may not be or only poorly available in a national court.

(9) In the case of contributory patent infringement, the UPC avoids weaknesses of some national legal systems that require a “double territoriality principle” (a contributory infringer can only be accused if both its supply of an essential element and the ultimately realized infringement of the claimed invention by someone else both occur in the territory of the same state). The UPC system, on the other hand, facilitates effective enforcement against both the supplier and the direct infringer, because it is sufficient that both delivery and direct infringement take place somewhere in the entire UPC territory. This is a clear strategic advantage, especially in the situation of pan-European supply chains that is frequently found today.

(10) The successful plaintiff recovers part of his legal costs if he wins the case. The amount of reimbursement is determined by reasonable costs of the party’s representative; it is capped depending on value of action (e.g. if value of action is 1 million, then up to 112,000 EUR may be reimbursed).

Table 3: Costs for 1st instance proceedings at the UPC

| Type of Proceedings | UPC court fees | ||

|

Infringement |

Fixed fee: 11,000 EUR |

optionally plus value-based fee depending on | |

| value of action, e.g. 500,000 EUR 1,000,000 EUR 5,000,000 EUR |

additional fee 0 EUR 8,000 EUR 32,000 EUR |

||

| Nullity | Fixed fee: 20,000 EUR | – | |

| Preliminary injunction | Fixed fee: 11,000 EUR | ||

However, the UPC also carries risks and potentially leads to disadvantages, so that patent applicants and owners might be more inclined to classical patents and requesting opt-out:

(1) The main disadvantage is the risk that a central attack to validity is possible and can thus lead to total revocation in the entire UPC area with a single decision. The classical EP patent system, on the other hand, allows further strategic options even if validity could be denied only in one country but affirmed in another.

(2) A deadline of only 2 months to prepare and file a response to a nullity attack is quite short to react. Appropriate representation of the proprietor is important to ensure fast processing without delay, to make full use of the response term.

(3) An earlier national right (i.e. prior art according to Art. 54(3) EPC, which has an earlier priority in relation to the unitary patent in dispute, but was published after the priority/filing date of the patent in dispute) has novelty-destroying effect vis-à-vis the unitary patent in the entire UPC area. Whereas in the context of classical EP patents, the earlier right is novelty-destroying only in the same country and if the EP patent was validated there.

(4) A central attack on validity is also possible following or even in parallel with opposition proceedings at the EPO. A central revocation action is possible as an independent action or as an invalidity counterclaim during infringement proceedings.

(5) A lack of guidance from case law in the initial phase, as the UPC will need time to develop its case law and clarify the many unclear details of the new system.

Various factors thus play a role in the decision for or against an opt-out; the advantages and disadvantages of the new and the known systems must be weighed against each other, and a decision made from this for all or part of one’s own patent portfolio. If the benefits of effective, “Europe-wide” and relatively inexpensive litigation, the broader choice of forums or legal enforcement against several defendants – possibly linked via supply chains – are in the foreground, the advantages of the new UPC system could tip the balance. If, on the other hand, one fears centralized attacks on validity and thus the risk of a complete loss of the patent in one legal action, especially in the case of important patents, one will, as a precaution, tend to avoid the UPC and therefore favours opt out.

The development of case law on patent infringement cases as well as harmonization through the new UPC will help to make the right decision for one or the other system in the consideration of the individual case. Whereby a temporally staggered and differentiated strategy makes a good combination possible: by opting out, first wait for the legal development in a state of low risk of total revocation and observe the competitive situation; if the new UPC legal framework proves to be legally secure and its advantages in procedural questions are confirmed, or if patent infringements are acutely recognizable, then a change to the UPC system is possible by a simple request for withdrawal of the opt-out (opt back-in). However, this should be well considered, as a renewed opt-out is no longer possible after an opt-in change.

Ultimately, it is a decision for each individual case. Depending on the specific case, important considerations are in favour of the new UPC system:

Importantly, the decision phase in favour or against (opt-out) the UPC goes beyond the initial sunrise period, as it should also be carried out on an ongoing basis for current and future EP applications and granted patents.

The decision as to whether the European patent will ultimately take the form of a unitary patent or whether it will be validated nationally should thus also take into account the aspects of the desired court system. Only validated EP-patents can be opted out. If the applicant on the other hand decides in favour of the unitary patent, an opt-out is not possible; the UPC system is then mandatory. An opt-out request made earlier will then become ineffective. In this respect, there is a connection between the decisions for or against unitary patent, and for or against UPC. That is, the decision for or against a unitary patent – especially at the time of patent grant – should already take into account possible infringement and validity issues that may arise in future. Consideration should also be given to where the current and future relevant markets are, where infringement might occur, and whether cross-border enforcement would be desirable.

Applicants should also be aware of different filing strategies to mitigate the risks of the new system. For example, it may make sense to keep a divisional application pending as a fallback position for important European patent families. The parent patent can be validated nationally while the divisional application can go into the new system (or vice versa) to allow more flexibility in litigation strategy. It should also be noted that several European countries allow double protection, i.e. national patents may exist besides unitary patents, even if/insofar the claimed scope is the same.

Further to Part 1: (I) Introduction and Overview

Further to Part 3: (III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

(I) Introduction and Overview

Introduction

June 1, 2023 marks the beginning of a new era in European patent law: the new European Unitary Patent system entered into force, consisting of the Unitary Patent (UP) and the Unified Patent Court (UPC). 50 years after the introduction of the European Patent Convention and millions of European patents filed, this may be the most prominent change in European patent practice. The Unitary Patent adds as a third pillar to the classical European patents and the national patents. The Unified Patent Court will have an influence on both the unitary patent and the classical European patents as a modern and efficient litigation system.

What will be new, what will remain? As the patent landscape in Europe becomes more complex, other relevant questions arise: what strategic decisions need to be made? How should patent applicants and owners adapt their practice, and what impact can be expected when flanking business in Europe by patent-protected innovation? This article is intended to provide guidance in answering such and other questions and, where appropriate, to draw a comparison with the established German/European litigation regime.

Key points of the new Unified Patent (UP) and Unified Patent Court (UPC) system

Type of protection

With the introduction of the new legal framework, the patent applicant at the European level (i.e. besides the national patents) has the possibility to choose between

(a) the new European patent with unitary effect (“unitary patent” / UP) in the territories of all participating EU member states which have ratified the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA), and

(b) as before, the “classical” European patent, which is a bundle patent and, after grant of the patent, is divided into national parts for the ultimately desired validated countries. If additional protection is sought for individual countries not covered by the unitary patent according to (a) (e.g. the non-EU countries Great Britain or Switzerland), a mixture of (a) and (b) need to be chosen.

The option to choose will be exercised at the time of grant, within a period of 1 month after the publication of the grant. Until grant, the procedure before the European Patent Office is the same, independent of the later choice of the type of protection. This means that the formal, procedural, and substantive requirements are the same, regardless of whether a unitary patent or a classically validated patent is concerned.

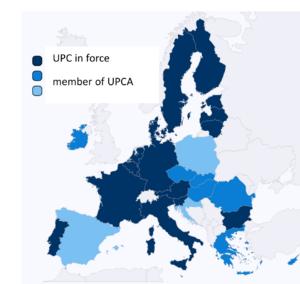

Currently, the EU member states shown in the map of Fig. 1 and listed below are covered by the new European patent with unitary effect:

Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Portugal, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Bulgaria

The map on the right shows the respective status of the EU states, depending on whether the UPCA is effective for them (dark blue), whether they have signed the Convention signed but not yet ratified the ratified the treaty (medium blue), or have not signed the treaty (light blue).

It remains to be seen whether the remaining EU member states which have signed but not yet ratified will do so and will ratify the UPCA, and whether Spain, Poland and Croatia, which have so far not acceded to the UPC, will change their position in the future in order to ultimately help the European Unitary Patent system achieve a full EU-wide unitary regime.

Interaction between EPO/EPC and UP/UPC

Up to the grant stage of a European Patent Application, everything remains the same as before. In particular, the European Patent Office (EPO) will remain competent for search and examination. Only at the grant stage the Applicant can choose between a classical validation or a UP, or a mixture of both (UP and validation in countries not party to the UPCA). Opposition before the EPO will remain to exist, no matter whether a UP and/or classical validated EP patent is involved.

The newly introduced Unified Patent Court (UPC) is a common court of the participating EU Member States and contracting states of the UPCA. An important difference to the type of protection is that the UPC has jurisdiction not only over unitary patents but also over classical European patents which have been validated in one or more states, provided that the classical EP patent is not opted out (as discussed later) and the validated country is also an UPCA state. The most significant change for litigation practice is that a decision of the UPC has uniform effect in all participating EU member states.

If the patent applicant chooses the UP as the type of protection at the time of grant, the UPC is mandatory in the participating EU countries. For classical European patents, however, the patent proprietor has the possibility during a 7-year transitional period to exclude the applicability of the UPC by a so-called “opt-out” request; then the old system of national litigation rules remains applicable.

Table 1 summarizes the tasks and competences between EPO and UPC

| European Patent Office | Unified Patent Court* | |

| Filing

Examination Grant Opposition Appeal |

Unitary Patent (UP) | Infringement Action (PI and main proceedings)Declaratory Action of Non-infringementNullity/Revocation Action |

| validated EP patent* | ||

* the UPC has competence also for classical validated EP patent, unless opted out

Table 2 lists pros and cons for choosing either UP or validation of the EP patent in individual countries. The patent owner’s decision for the one or the other system includes a weighing of pros and cons depending on the individual case.

| Pro | Contra | |

|

Unitary Patent (UP) |

unitary protection in the whole territory of UPCA countries

more simple administration less annuity fee compared to a total of sum of 4 or more countries enforcement in 1 efficient UPC court proceedings harmonized substantive and procedural law |

validation of patent in non-UPCA states is still needed if scope of UP territory is not sufficient

during transition phase a complete translation of the patent specification into one other EU language is needed all or none in terms of maintenance (annuity payments) and validity (risk of total nullity) |

|

validated EP patent |

still cost-efficient if number of desired countries is relatively low (1 to 3)

abandonment of individual countries while maintaining others is possible (cost factor) |

More administrative burden

enforcement in every country needed where infringement takes place |

Further positive or critical effects will become apparent below when details of the new system and factors to opt into or out of the new law will be discussed.

Procedural law in the new Unified Patent Court (UPC)

The rules of procedure of the Unified Patent Court are similar to the basic structures and procedures of German court proceedings. However, there are special features in the UPC which should be taken care of:

Thus, it is clear that while the patent landscape and litigation in Europe will be made more complex by the new European Unitary Patent and the new Unified Patent Court, these instruments effectively open up additional means and ways of a centralized, effective and relatively inexpensive system for obtaining and enforcing rights. However, achieving the strategic goals will require more than ever good preparation and attention to the peculiarities and tight time regime in the new litigation law.

Further to Part 2: (II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

Further to Part 3: (III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

Years of planning finally become reality: The official starting signal has now been given! Germany ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPC) on February 17, 2023.

This means that the final requirements for the entry into force of the Agreement and thus for the start of the Unified Patent Court on June 1, 2023 have been met. As previously reported, the testing phase for the Unified Patent Court’s file management and communication software is already underway, and from March 1, 2023 the sunrise period for filing any opt-out requests will begin.

For more information, please visit: https://www.bmj.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2023/0217_Einheitliches_Patentgericht.html

According to the current schedule, the Unified Patent Court will start its work on June 1, 2023.

The so-called sunrise period, during which opt-out requests can be filed with the Unified Patent Court for granted European patents or published European patent applications will start on March 1, 2023, according to the current planning of the Unified Patent Court.

An opt-out request is only effective if it is entered in the register of the Unified Patent Court.

At present, it is not yet known how long it will take from filing the opt-out request to registration, as there are no empirical values yet. In a test phase for the file management and communication software of the Unified Patent Court, which will start on February 13, 2023, we will be able to test the process of filing the request, but this does not allow us to draw any firm conclusions on the subsequent processing time of opt-out requests at the Unified Patent Court.

We therefore recommend filing any opt-out requests as early as possible starting from March 1, 2023.

Now is the time to review again your patent portfolio of European patents and published European patent applications and to decide for which patents/patent applications an opt-out request should be filed early.

Do you have any further questions on this topic or on the Unified Patent Court and the Patent with Unitary Effect?

Please do not hesitate to contact us, we will be happy to advise you!

Dr. Dorothea Hofer

European and German Patent, Trademark and Design Attorney

“All good things are worth waiting for”. Now the time has finally come:

The Unified Patent Court has announced on its website that it plans to commence operations on April 1, 2023.

This means: Actions for invalidity and for infringement of European patents can then be filed with the Unified Patent Court, unless a request to “opt-out” from the Unified Patent Court system has been filed for the European patent in question.

Such an “opt-out” request can be filed as early as January 1, 2023, i.e. in the sunrise period before April 1, 2023. The “opt-out” request can be filed for granted European patents as well as for pending European patent applications that have already been published.

In addition, for granted European patents where the mention of grant is published on or after April 1, 2023, a request for unitary effect of the European patent for all participating member states that have joined the unitary patent system can be filed within one month of publication.

The participating states – as of October 2022 – are so far the following 17 states:

Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia, Sweden

In the foreseeable future, the following additional member states could join as soon as they have completed the pending ratification: Ireland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Greece and Cyprus.

For other member states, such as Spain or Croatia, the European patent must still be validated nationally. The same applies, of course, to all non-EU states that belong to the European Patent System (such as Great Britain, Norway, Switzerland, Türkiye, etc.). Instead of the European patent with unitary effect, there will of course also be the possibility in the future for patent protection to extend only to certain desired countries, as in the past, by means of corresponding validation. Depending on whether unitary effect or classical validation is chosen, different translation requirements have to be fulfilled for the granted patent.

For European patent applications for which the intention to grant has already been communicated, i.e. the communication according to R. 71(3) EPC has been issued, the possibility to obtain a European patent with unitary effect can be opened by the following measures:

* An early request for the European patent with unitary effect can be filed. The EPO will deal with the request from April 1, 2023. Or:

* A request is filed in response to the communication under R. 71(3) EPC to defer grant. The EPO then delays the grant so that it is not published until on or after April 1, 2023.

Both measures can be applied as soon as Germany has deposited the certificate of ratification. This date is yet to be announced.

Now is a good time to review the current portfolio of European patents and European patent applications to determine whether an “opt-out” request should be filed for all or some, or whether a European patent with unitary effect is desired for pending applications. This decision will depend on many factors, including the importance of the invention, the technical field, the competitive environment, etc.

Please contact us. We will be happy to advise you on which solution is best for you.

Dr. Dorothea Hofer, Jürgen Feldmeier LLM, Dr. Andreas Oser LLM

As previously reported, following ratification in Germany, the way is cleared for the European patent with unitary effect (EU unitary patent) and the Unified Patent Court (UPC). As a result of the deposit of the instrument of ratification by Austria on 18 January 2022, the “provisional application of the EPC/UPC” has now entered into force. Only the preparatory work for the establishment of the court system will have to be completed in the coming months. The Preparatory Committee estimates that it will take at least 8 months. Once the UPC has become effective, Germany will deposit its instrument of ratification as the last formal act, which will automatically trigger the starting point: at the beginning of the fourth following month, i.e. probably towards the end of 2022 or the beginning of 2023, the unitary patent and the UPC will finally become reality, after a long waiting period.

What does this mean for patent applicants and patent proprietors of European patents?

The following are some points to consider now, i.e. even before entering into force:

(1) Choice between the new unitary patent and the classical EP patent

Even if the option can in principle only be exercised after entry into force: by means of suitable procedural measures, this freedom of choice could still be used for EP applications currently pending before the EPO, even if the grant phase is already relatively far advanced.

In a recent communication from the European Patent Office, official measures are announced – without giving details at the moment – to give patent applications that are about to be granted the chance to obtain a unitary patent. The communication on the version of the patent application intended for grant (the so-called “Rule 71(3) Communication”) is considered to be the caesura for the applicability of these announced measures.

If you wish to maintain the option for applications although a Rule 71(3) Communication has already been issued, you may have to take your own procedural steps. That is, in order to gain time in this situation, for instance minor formal amendments to the intended text could be requested at the end of the regular 4-month period, in order to trigger a second 71(3) Communication. Alternatively, or in addition, it is also possible to continue the application after the due date for completion of the (possibly second) Rule 71(3) Communication has deliberately expired: after being notified of a loss of rights, further processing (with an official fee of 265.00 EUR) would then have to be requested.

(2) Choice depending on the type and number of countries desired

After entry into force of the Unitary Patent Act, the applicant must decide, at the latest one month after receipt of the decision to grant by the EPO, whether to proceed with EP validations in individual countries as before or to seek the new EU unitary patent. The new EU unitary patent would allow patent protection over the entire territory of the participating EU countries at one stroke, which currently includes the following 17 countries: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, Slovenia and Sweden. More will be added soon, as 8 countries only need to ratify (Czech Republic, Greece, Ireland, Poland, Romania, Slovakia, Hungary, Cyprus). If protection is to be achieved for further, non-participating countries – including non-EU states of the EPC such as Great Britain or Switzerland – additional national validations would have to be carried out there in accordance with the “old” model.

(3) Choice of (non-)applicability of the UPC (opt-in/opt-out)

Three months before the unitary patent and the UPC enter into force, the so-called “sunrise period” begins. From this time onwards, the applicant/patent proprietor can request the non-applicability of the UPC system for one or more or even all of his existing and future classical EP patents by “opting out”. In the opt-out state, individual national courts will then – during a transitional period of 7 years – retain jurisdiction as before in actions on patent infringement and validity in the respective country. Reasons for choosing the opt-out are, for example, not to expose the patent to the risk of a central invalidation through a single nullity procedure; furthermore, in the opt-out state, the development and the practice and case law in the new UPC system could first be observed; if sufficient legal certainty is given, the patent proprietor can then enable UPC applicability again in the future as a result of an opt-in declaration.

(4) Choice of a competent UPC court location for patent infringements

Due to their experience, the German court locations Düsseldorf, Munich, Mannheim and Hamburg will also play an important role in the new UPC system. The court location Germany could be further strengthened by the fact that the central UPC court in Munich is not only responsible for the field of mechanics, as originally stipulated, but may also awarded the technical fields of chemistry, pharmaceuticals and human necessities (incl. health care); this field was originally intended for London, but is now available for disposition as a result of Brexit.

If there is no opt-out, the decisions of the UPC court will be directly effective in all countries where the EP patent exists.

If you have any questions, please do not hesitate to contact our team. Dr Andreas Oser, LL.M. (office@pruefer.eu)