We are delighted to announce that our partner Dr. Peter Klein has obtained the European Patent Litigation Certificate issued by the University of Maastricht in cooperation with the Academy of European Law (ERA) in Trier. This includes an extensive practical and theoretical training in the law underlying the Unified Patent Court (#UPC) and related fields of European law so that he is well prepared for representing clients in all proceedings before the Unified Patent Court.

On 1 September 2024, ROMANIA will become the 18th member state of the UPC. The ratification of the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPCA) was signed on 31 May 2024. The whole article can be read here.

Before the Paris Local Division, in a case where the defendant had forced an intervener into the proceedings pursuant to Rule 316A RoP (forced intervention), the intervener has obtained a period of one month for filing its Application to Intervene as well as for filing its Statement in Intervention. Contrary to Rule 316.2 RoP, which mentions a “further period” for filing the Statement in Intervention, the Court did not set any such further period.

Incidentally, the intervener’s one-month period for filing its Application to Intervene and its Statement in Intervention expired on March 19, 2024, which is almost identical to the end of the defendant’s three-month period for filing its Statement of Defence (March 18, 2024). The defendant’s Statement of Defence did not include a counterclaim for revocation of the patent.

The Court held that the intervener may not develop claims contrary to those of the party he supports and may not autonomously develop claims and procedural modalities different from those offered to the party it supports. Therefore, since the defendant’s term for filing a counterclaim also applies to the intervener, the intervener is not entitled to pose an own counterclaim after that term has expired. It would appear that, although not expressly stated, the Court considered that, in principle, an own counterclaim of the intervenient is admissible, albeit subject to the defendant’s terms.

In addition, the Court again rejected a request to change the language of the proceedings from French to English even though the language of the patent in question is English and the defendant itself, a French company and the only French party involved, previously and unsuccessfully had requested a change of the language of the proceedings from French to English. This shows that the bar for changing the language is very high.

Case number UPC_CFI_440/2023, order date May 6, 2024

In our view, the Court did not take sufficient account of the situation of the forced intervention. It is already challenging to set up a properly researched counterclaim of revocation within the three months granted to the defendant. To do so within one month could be considered outright impossible, especially as cooperation in a forced intervention cannot be expected. A corresponding obligation for the short term raises constitutional concerns.

Still, the possibility of a separate revocation action remains.

The first decisions of the UPC have been handed down, and it will be exciting to learn the position of the UPC regarding the much-discussed issues of claim interpretation, the burden of presentation and proof for facts, and also regarding inventive step considerations.

1. Claim interpretation – introduction and comparison with the EPO

It is an ongoing debate in proceedings before the EPO, to what extent the description should be considered for claim interpretation, and the underlying legal basis, if any.

In decision T 1473/19, the Board of Appeal (BoA) came to the conclusion that Art. 69 EPC in conjunction with Art. 1 of the Protocol for its interpretation can be relied upon regarding claim interpretation and determining the claims’ scope, both in examination proceedings and in opposition proceedings. Further, although according to Art. 69 EPC, 2nd sentence, description and drawings shall be used to interpret the claims, there is still the primacy of the claims (1st sentence of Art. 69 EPC, according to which the extent of the protection covered by a European patent or patent application shall be determined by the claims), which sets the limits for interpreting claim features.

It was further decided that the description may additionally be consulted to further interpret the claim, even if the claim is clear from itself.

However, as an unambiguous (clear) claim wording must be given priority over the description for interpretation of claim features because of the “primacy of the claims”-principle, consulting the description for claim interpretation is eventually only possible for ambiguous claim features.

In T 0169/20, the Board concluded that the provisions of Art. 84 EPC, particularly 2nd sentence of Art. 84 EPC, and Rules 42 and 43 EPC provided an adequate legal basis for claim interpretation when assessing patentability. Art. 69 EPC was only used to determine the scope of protection for the purpose of examining conformity with Art. 123(3) EPC, and in infringement proceedings (contrary to T 1473/19). The Board further concluded that “if the wording of a claim is clear and technically reasonable in itself, it is neither necessary nor justified to interpret it in the light of the description. In particular, the support of the description should not be used for restricting or modifying the subject-matter of the invention beyond what a skilled person would understand when reading the wording of the claims, for example by excluding interpretations which are both reasonable and technically sensible within the relevant technical context.“ (underlining added).

In summary, although both exemplary decisions of the Boards of Appeal of the EPO apply a different legal basis (Art. 69 EPC in conjunction with Art. 1 of the Protocol thereto, and Art. 84 EPC in combination with Rules 42 and 43 EPC), the outcome is similar: It is the wording of the claims which defines the claimed subject-matter, and the description may only be used to interpret ambiguous features.

Now the UPC handed down the first orders, and it will be interesting to see the position of the UPC regarding claim interpretation:

In decision UPC_CoA_335/2023 (rectified), the Court of Appeal (CoA) of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) decided that “the patent claim is not only the starting point, but the decisive basis for determining the protective scope of a European patent under Art. 69 EPC in conjunction with the Protocol on the Interpretation of Art. 69 EPC.” (Headnote 2, 1st sentence). Further, the CoA of the UPC came to the remarkable conclusion that “the description and the drawings must always be used as explanatory aids for the interpretation of the patent claim and not only to resolve any ambiguities in the patent claim.” (emphasis added; Grounds for the Order, 5.d) aa); 3rd paragraph). This is different from the position of the EPO’s BoA, which held that consulting the description for claim interpretation is only possible for ambiguous claim features. The CoA of the UPC further stated that it is the aim of the claim interpretation to “combine adequate protection for the patent proprietor with sufficient legal certainty for third parties.” (Grounds for the Order, 5.d) aa), 6th paragraph).

In decision UPC_CoA_335/2023, the CoA held that some of the features of claim 1 required interpretation, such as the feature “cell or tissue sample”. This point was actually relevant in the court proceedings, because interpreting this feature was relevant in assessing substantive patentability, notably by questioning: can a sample extracted from a cell or tissue but bound to a support be considered as the claimed “cell or tissue sample”? According to the CoA, the feature required that a cell or tissue sample is to be understood as a sample which is still recognisable as a cell or tissue. Additionally, the CoA additionally consulted the description which supported this understanding.

To sum up, the CoA of the UPC takes the position that based on Art. 69 EPC in conjunction with the Protocol on the Interpretation of Art. 69 EPC the description must always be considered for claim interpretation, not only if claim features are ambiguous.

2. The burden of presentation and proof for facts in preliminary injunctions

Pursuant to Rule 205 et seq. RoP, the order for provisional measures is issued by way of summary proceedings (commonly also referred to as preliminary injunction (PI) proceedings) in which the opportunities for parties to present facts and evidence is limited.

Up to now, national law and practice on PI proceedings were quite distinct among European countries, and even in German practice there was no harmonized approach [1].

According to the CoA, on the one hand, the standard of proof must not be set too high, in order to avoid irreparable harm to the patent proprietor that can result from delay, but on the other hand, it must not be set too low in order to prevent the defendant from being harmed by an order for provisional measure that is revoked at a later date.

According to R. 211.2 RoP, the applicant may be “required to provide reasonable evidence to satisfy the Court with a sufficient degree of certainty that the applicant is entitled to commence proceedings pursuant to Article 47, that the patent in question is valid and that his right is being infringed, or that such infringement is imminent.”

The CoA now held that such a “sufficient degree of certainty requires that the court considers it at least more likely than not that the Applicant is entitled to initiate proceedings and that the patent is infringed. A sufficient degree of certainty is lacking if the court considers it on the balance of probabilities to be more likely than not that the patent is not valid.” (Grounds for the Order, 5. a) 4th paragraph).

Hence, the CoA for the UPC ruled a “balance of probability“ assessment. In case it is more likely that a patent is invalid, a PI shall fail. This concept boils down to the “simple” question: is it more likely that the patent is held not novel or not inventive? In this case, the UP court shall not grant a PI in patent infringement proceedings.

This decision hence provides a common standard under the UPC, distinct from various conflicting decision among national courts.

3. Inventive step considerations before the UPC

In the case at issue, UPC_CoA_335/2023, the CoA came to the conclusion that it is more likely than not that the subject-matter of claim 1 will prove to be obvious. Interestingly, by this decision the CoA overruled the opposite finding of the court of first instance on that part.

The CoA based its conclusion on the finding that the only difference between the relevant prior art document D6 and claim 1 was that D6 did not disclose the feature that the method of claim 1 is intended to detect a plurality of analytes in a cell or tissue sample. Rather, D6 disclosed a method that was intended to detect “amplified DNA molecules” (ASMs), which were not present in a cell or tissue sample, and which would not be regarded by a skilled person as a cell or tissue sample within the meaning of the patent. Hence, novelty was acknowledged.

Regarding inventive step, the CoA further stated that a skilled person seeking to develop high-throughput optical multiplexing methods for detecting target molecules in a sample would have considered D6, as this document disclosed a method for detecting a plurality of ASMs. Starting from this document and having in mind that at the priority date there was a demand for multiplex analysis techniques, a skilled person would also consider transferring the method of D6 to an in situ environment, as evidenced by a further document (B30). Remarkably, in the reasoning why a skilled person, being confronted with difficulties, would not have been prevented from carrying out tests due to insufficient prospects of success, the CoA refers to the Swedish Intellectual Property Office Consulting Report (B10, p. 5).

The CoA concludes that it is more likely than not that the patent at issue will prove to be invalid in proceedings on the merits due to a lack of inventive step and rules that there is no sufficient basis for the issuance of a preliminary injunction.

Take home message:

[1] GRUR 2022, 811 – Phoenix Contact/Harting

Munich District Court:

Decisions of September 29, 2022, Az. 7 O 4716/22; and October 27, 2022, Az. 7 O 10295/22:

European patents and also the German parts of European patents are presumed to be valid from the date of publication of their grant

Düsseldorf District Court:

Decision of September 22, 2022, Az. 4 b O 54/22:

Questions presumption of validity of European patents and also the German part thereof

[2] German Supreme Court, BGH – Fulvestrant (X ZR 59/17; Headnotes)

The detailed article is published at JUVE Patent.

Since the introduction of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) in June 2023, a new system for central attacking the validity of and thereby to nullify a European Patent has been introduced. If a European patent of concern is an EU Unitary Patent, or if a classically validated European patent was not opted out from the competence of the UPC, a central revocation action under the UPC now exists in parallel to an opposition before the European Patent Office (EPO). Therefore, the question arises: what are the pros and cons of challenging the validity either before the EPO or before the UPC? The present report provides some guidance and discusses the main advantages and disadvantages of each system – which eventually is a matter of strategic considerations whether and which advantage may prevail – be it costs, timing, speed of proceedings, and possibly other issues.

We are delighted to announce that our managing partner Dr. Dorothea Hofer has obtained the European Patent Litigation Certificate issued by the University of Maastricht in cooperation with the Academy of European Law (ERA) in Trier. This includes an extensive practical and theoretical training in the law underlying the Unified Patent Court (#UPC) and related fields of European law.

(III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

Opposition proceedings before the European Patent Office (EPO) are an attractive forum for challenging patents; the procedure is virtually unrivaled worldwide in terms of value for money. The process is simple, streamlined and relatively inexpensive. The practice is well tested. However, there are restrictions and drawbacks – for example, a deadline of nine months after the grant date for submission, the long duration of the opposition and appeal proceedings, and strict rules for admitting evidence submitted late.

The UPC now offers a second chance by providing another forum for central revocation of a European patent throughout the territory of the UPC states. Moreover, revocation actions can be brought before the UPC at any time after grant, independently of opposition proceedings before the EPO. Therefore, it is indeed a (further) effective attack on the European patent, and even in case European opposition and appeal proceedings were already pending in parallel. In the German legal system, on the other hand, there is the restriction – besides the fact that it only acts against the German part of the European patent – that revocation proceedings are inadmissible as long as European opposition and appeal proceedings are still pending.

The opposition procedure at the EPO is essentially a written procedure with an oral hearing at the end; the oral hearing takes place before a three-member panel and may last a full day. The UPC follows a similar approach – a written procedure followed by an oral hearing. However, there is a tight timing in the invalidity proceedings before the UPC. The UPC requires the patent owner to file a response within two months (while the EPO sets a four-month deadline); then the plaintiff may file a reply to the response within two months, and the defendant (patent owner) may file a rejoinder to the reply within one month, limited to the points raised in the reply.

The faster procedure before the UPC may allow for tactics on the nullity plaintiff’s side that weren’t available before. This is because, whilst the plaintiff can prepare his facts and arguments (and potential counter-arguments) well in advance of lodging the action, pressure is put on the defendant (patent owner) with respect to time and effort. Therefore, an efficient interaction of the patent owner with his team of attorneys is important. If on the other hand the patent owner starts with an infringement action, pressure will rather lie on the side of the infringement defendant in case he seeks to raise a defence by counter-action of nullity; this is because the counter-action should then be lodged soon after the start of the infringement action for being considered during the infringement proceedings.

A difference is that filing an invalidity action at the UPC is more expensive than filing an opposition at the EPO: court fee amounts to 20 000 EURO, whereas at the EPO it is presently only 880 EURO. The costs at the UPC are comparable to filing a German nullity action – however with the difference that the decision is effective throughout the UPC territory.

Although the opposition divisions of the EPO could, in principle, order the parties to pay the costs, this very rarely happens in practice; the predominant rule is that each party bears its own costs. The UPC Rules of Procedure provide that a winning party is entitled to reimbursement of its costs insofar as these are reasonable and proportionate.

There is also a risk that matters before the UPC will become complicated if the validity of a European patent is challenged by a counterclaim to an infringement action. In opposition proceedings before the EPO, only the validity itself is examined – the EPO does not consider infringement at all.

However, there is also the possibility that the proceedings before the UPC are split into two – i.e. a bifurcated system like the one practiced in Germany – where infringement and the validity are decided separately by two different courts (the former by the Local Division, the latter by the Central Division).

While all isolated revocation actions are heard by a central chamber of the UPC, revocation counterclaims in response to infringement may instead be brought before the then competent local chamber of the UPC; however, it is at the discretion of the local chamber to refer the revocation counterclaim to the central chamber. Practice will show which principle – the one-track or the two-track procedure – will bring overall advantages before the UPC and possibly prevail in the long run.

As can be seen from this overview, there are similarities but also differences between the opposition procedure before the EPO and the nullity procedure before the UPC. Probably the most significant difference in practice is the relatively strict time regime foreseen for the proceedings before the UPC. This is especially true when the infringement and revocation counterclaims run concurrently and thus require effective and expeditious action by the parties and their representatives. However with the benefit of a decision within a short time.

Further to Part 1: (I) Introduction and Overview

Further to Part 2: (II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

(II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

During a seven-years transition phase, the jurisdiction of the future Unified Patent Court (UPC) can be declared inapplicable, by way of an opt-out request by the IP right holder, to a pending European patent application (“EP application”), to a granted European patent (“EP”), or to a supplementary protection certificate (“SPC”). This possibility was introduced to build confidence by users on the long run. If opted-out, disputes will then continue to be handled by national courts on a country-by-country basis. Once a European patent has been opted out, it is excluded from the jurisdiction of the UPC for its entire life.

Opt-outs are not possible for unitary patents.

Opt-out requests are free of official fees and can be filed by IP right owners or by representatives admitted to the UPC. To reduce costs, mass requests on the basis of lists is recommended, using software specially developed for this purpose to reduce administrative measures on the part of attorneys. It is important to ensure that the opt-out request correctly identifies all actual owners of IP rights; the owners entered in the EPO register may not currently be the correct ones. In case of doubt, it is advisable to compare the data with official registers, e.g. to detect changes or transfers of rights in the meantime. An originally undetected inaccuracy could still be objected years later in a legal dispute, and an originally invalid opt-out may lead to the undesired applicability of the UPC.

There is a time limitation for the opt-out request: if an action is received by the UPC, e.g. in the form of a revocation action, a subsequent opt-out has no effect. On the other hand, it may make sense – for example, if circumstances or strategy change, see considerations below – to make the opted-out EP patent later accessible to the UPC by withdrawing the opt-out (opt-back-in).

An opt-out for a divisional application is independent of that for the parent application.

Advantages and disadvantages of the UPC – what speaks for an opt-out, what against?

Numerous factors in general and in particular will influence the decision whether for certain patents the benefits of the UPC outweigh the disadvantages, or whether it is better to opt out.

The advantages and benefits of the UPC outweigh the disadvantages if the following objectives are pursued:

(1) A unitary decision allows enforcement in all participating (currently 17, likely more in the future) EU countries with a single infringement action. This advantage comes into play especially when acts of infringement take place in several countries. This advantage is limited when non-participating countries are involved, such as non-EU countries like the UK or Switzerland, where infringement proceedings might still have to be brought specifically. However, these adverse effects could be neutralized again, for example, if a number of UPC states are nevertheless affected or if the remaining national courts follow the UPC judgment, or if the UPC judgment favours a party settlement; due to the speedy procedure at the UPC, it can be expected that the UPC judgment will be available first.

(2) In addition to the corresponding procedural and substantive unification and simplification, the enforcement of patents in large parts of Europe is achieved at relatively lower costs. The winning party get its costs reimbursed at least partially. Some selected cost items of UPC proceedings are listed in Table 3 below.

(3) The duration of proceedings per instance is expected to be only 12-14 months from the initiation of the proceedings to the judgment.

(4) Patent owners usually get a free choice of an appropriate venue, especially if an active rather than passive/defensive strategy is pursued. It may be expected that the four German local courts of the UPC with their competence will have a high attraction especially for patent owners. The Munich based central court has received more competence: following withdrawal of the London central court, it will now decide on chemical cases, in addition to patents pertaining to the mechanical field already allocated previous.

(5) The UPC decides with the involvement of technical judges. This can and will probably help to clarify the facts, especially in the case of technically demanding patents. In line with this favourable new feature: European patent attorneys, in case of having an appropriate additional legal qualification are now admitted to represent as a single counsel at the UPC. Thus, with the additional technical competence on both the judge’s and the representative’s side, communications “at eye level” with this panel of judges can be expected – an important advantage especially in oral proceedings.

(6) The use of a uniform language, such as English as an international standard.

(7) The expected harmonization of Europe-wide dispute regulation. And thus the avoidance of poorly predictable, country-specific case law in national courts.

(8) Effective evidence-gathering procedures, such as inspections, are possible that may not be or only poorly available in a national court.

(9) In the case of contributory patent infringement, the UPC avoids weaknesses of some national legal systems that require a “double territoriality principle” (a contributory infringer can only be accused if both its supply of an essential element and the ultimately realized infringement of the claimed invention by someone else both occur in the territory of the same state). The UPC system, on the other hand, facilitates effective enforcement against both the supplier and the direct infringer, because it is sufficient that both delivery and direct infringement take place somewhere in the entire UPC territory. This is a clear strategic advantage, especially in the situation of pan-European supply chains that is frequently found today.

(10) The successful plaintiff recovers part of his legal costs if he wins the case. The amount of reimbursement is determined by reasonable costs of the party’s representative; it is capped depending on value of action (e.g. if value of action is 1 million, then up to 112,000 EUR may be reimbursed).

Table 3: Costs for 1st instance proceedings at the UPC

| Type of Proceedings | UPC court fees | ||

|

Infringement |

Fixed fee: 11,000 EUR |

optionally plus value-based fee depending on | |

| value of action, e.g. 500,000 EUR 1,000,000 EUR 5,000,000 EUR |

additional fee 0 EUR 8,000 EUR 32,000 EUR |

||

| Nullity | Fixed fee: 20,000 EUR | – | |

| Preliminary injunction | Fixed fee: 11,000 EUR | ||

However, the UPC also carries risks and potentially leads to disadvantages, so that patent applicants and owners might be more inclined to classical patents and requesting opt-out:

(1) The main disadvantage is the risk that a central attack to validity is possible and can thus lead to total revocation in the entire UPC area with a single decision. The classical EP patent system, on the other hand, allows further strategic options even if validity could be denied only in one country but affirmed in another.

(2) A deadline of only 2 months to prepare and file a response to a nullity attack is quite short to react. Appropriate representation of the proprietor is important to ensure fast processing without delay, to make full use of the response term.

(3) An earlier national right (i.e. prior art according to Art. 54(3) EPC, which has an earlier priority in relation to the unitary patent in dispute, but was published after the priority/filing date of the patent in dispute) has novelty-destroying effect vis-à-vis the unitary patent in the entire UPC area. Whereas in the context of classical EP patents, the earlier right is novelty-destroying only in the same country and if the EP patent was validated there.

(4) A central attack on validity is also possible following or even in parallel with opposition proceedings at the EPO. A central revocation action is possible as an independent action or as an invalidity counterclaim during infringement proceedings.

(5) A lack of guidance from case law in the initial phase, as the UPC will need time to develop its case law and clarify the many unclear details of the new system.

Various factors thus play a role in the decision for or against an opt-out; the advantages and disadvantages of the new and the known systems must be weighed against each other, and a decision made from this for all or part of one’s own patent portfolio. If the benefits of effective, “Europe-wide” and relatively inexpensive litigation, the broader choice of forums or legal enforcement against several defendants – possibly linked via supply chains – are in the foreground, the advantages of the new UPC system could tip the balance. If, on the other hand, one fears centralized attacks on validity and thus the risk of a complete loss of the patent in one legal action, especially in the case of important patents, one will, as a precaution, tend to avoid the UPC and therefore favours opt out.

The development of case law on patent infringement cases as well as harmonization through the new UPC will help to make the right decision for one or the other system in the consideration of the individual case. Whereby a temporally staggered and differentiated strategy makes a good combination possible: by opting out, first wait for the legal development in a state of low risk of total revocation and observe the competitive situation; if the new UPC legal framework proves to be legally secure and its advantages in procedural questions are confirmed, or if patent infringements are acutely recognizable, then a change to the UPC system is possible by a simple request for withdrawal of the opt-out (opt back-in). However, this should be well considered, as a renewed opt-out is no longer possible after an opt-in change.

Ultimately, it is a decision for each individual case. Depending on the specific case, important considerations are in favour of the new UPC system:

Importantly, the decision phase in favour or against (opt-out) the UPC goes beyond the initial sunrise period, as it should also be carried out on an ongoing basis for current and future EP applications and granted patents.

The decision as to whether the European patent will ultimately take the form of a unitary patent or whether it will be validated nationally should thus also take into account the aspects of the desired court system. Only validated EP-patents can be opted out. If the applicant on the other hand decides in favour of the unitary patent, an opt-out is not possible; the UPC system is then mandatory. An opt-out request made earlier will then become ineffective. In this respect, there is a connection between the decisions for or against unitary patent, and for or against UPC. That is, the decision for or against a unitary patent – especially at the time of patent grant – should already take into account possible infringement and validity issues that may arise in future. Consideration should also be given to where the current and future relevant markets are, where infringement might occur, and whether cross-border enforcement would be desirable.

Applicants should also be aware of different filing strategies to mitigate the risks of the new system. For example, it may make sense to keep a divisional application pending as a fallback position for important European patent families. The parent patent can be validated nationally while the divisional application can go into the new system (or vice versa) to allow more flexibility in litigation strategy. It should also be noted that several European countries allow double protection, i.e. national patents may exist besides unitary patents, even if/insofar the claimed scope is the same.

Further to Part 1: (I) Introduction and Overview

Further to Part 3: (III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

(I) Introduction and Overview

Introduction

June 1, 2023 marks the beginning of a new era in European patent law: the new European Unitary Patent system entered into force, consisting of the Unitary Patent (UP) and the Unified Patent Court (UPC). 50 years after the introduction of the European Patent Convention and millions of European patents filed, this may be the most prominent change in European patent practice. The Unitary Patent adds as a third pillar to the classical European patents and the national patents. The Unified Patent Court will have an influence on both the unitary patent and the classical European patents as a modern and efficient litigation system.

What will be new, what will remain? As the patent landscape in Europe becomes more complex, other relevant questions arise: what strategic decisions need to be made? How should patent applicants and owners adapt their practice, and what impact can be expected when flanking business in Europe by patent-protected innovation? This article is intended to provide guidance in answering such and other questions and, where appropriate, to draw a comparison with the established German/European litigation regime.

Key points of the new Unified Patent (UP) and Unified Patent Court (UPC) system

Type of protection

With the introduction of the new legal framework, the patent applicant at the European level (i.e. besides the national patents) has the possibility to choose between

(a) the new European patent with unitary effect (“unitary patent” / UP) in the territories of all participating EU member states which have ratified the Unified Patent Court Agreement (UPCA), and

(b) as before, the “classical” European patent, which is a bundle patent and, after grant of the patent, is divided into national parts for the ultimately desired validated countries. If additional protection is sought for individual countries not covered by the unitary patent according to (a) (e.g. the non-EU countries Great Britain or Switzerland), a mixture of (a) and (b) need to be chosen.

The option to choose will be exercised at the time of grant, within a period of 1 month after the publication of the grant. Until grant, the procedure before the European Patent Office is the same, independent of the later choice of the type of protection. This means that the formal, procedural, and substantive requirements are the same, regardless of whether a unitary patent or a classically validated patent is concerned.

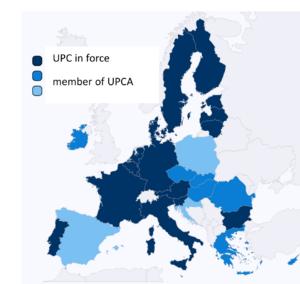

Currently, the EU member states shown in the map of Fig. 1 and listed below are covered by the new European patent with unitary effect:

Germany, France, Italy, Austria, Portugal, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Austria, Slovenia, Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Bulgaria

The map on the right shows the respective status of the EU states, depending on whether the UPCA is effective for them (dark blue), whether they have signed the Convention signed but not yet ratified the ratified the treaty (medium blue), or have not signed the treaty (light blue).

It remains to be seen whether the remaining EU member states which have signed but not yet ratified will do so and will ratify the UPCA, and whether Spain, Poland and Croatia, which have so far not acceded to the UPC, will change their position in the future in order to ultimately help the European Unitary Patent system achieve a full EU-wide unitary regime.

Interaction between EPO/EPC and UP/UPC

Up to the grant stage of a European Patent Application, everything remains the same as before. In particular, the European Patent Office (EPO) will remain competent for search and examination. Only at the grant stage the Applicant can choose between a classical validation or a UP, or a mixture of both (UP and validation in countries not party to the UPCA). Opposition before the EPO will remain to exist, no matter whether a UP and/or classical validated EP patent is involved.

The newly introduced Unified Patent Court (UPC) is a common court of the participating EU Member States and contracting states of the UPCA. An important difference to the type of protection is that the UPC has jurisdiction not only over unitary patents but also over classical European patents which have been validated in one or more states, provided that the classical EP patent is not opted out (as discussed later) and the validated country is also an UPCA state. The most significant change for litigation practice is that a decision of the UPC has uniform effect in all participating EU member states.

If the patent applicant chooses the UP as the type of protection at the time of grant, the UPC is mandatory in the participating EU countries. For classical European patents, however, the patent proprietor has the possibility during a 7-year transitional period to exclude the applicability of the UPC by a so-called “opt-out” request; then the old system of national litigation rules remains applicable.

Table 1 summarizes the tasks and competences between EPO and UPC

| European Patent Office | Unified Patent Court* | |

| Filing

Examination Grant Opposition Appeal |

Unitary Patent (UP) | Infringement Action (PI and main proceedings)Declaratory Action of Non-infringementNullity/Revocation Action |

| validated EP patent* | ||

* the UPC has competence also for classical validated EP patent, unless opted out

Table 2 lists pros and cons for choosing either UP or validation of the EP patent in individual countries. The patent owner’s decision for the one or the other system includes a weighing of pros and cons depending on the individual case.

| Pro | Contra | |

|

Unitary Patent (UP) |

unitary protection in the whole territory of UPCA countries

more simple administration less annuity fee compared to a total of sum of 4 or more countries enforcement in 1 efficient UPC court proceedings harmonized substantive and procedural law |

validation of patent in non-UPCA states is still needed if scope of UP territory is not sufficient

during transition phase a complete translation of the patent specification into one other EU language is needed all or none in terms of maintenance (annuity payments) and validity (risk of total nullity) |

|

validated EP patent |

still cost-efficient if number of desired countries is relatively low (1 to 3)

abandonment of individual countries while maintaining others is possible (cost factor) |

More administrative burden

enforcement in every country needed where infringement takes place |

Further positive or critical effects will become apparent below when details of the new system and factors to opt into or out of the new law will be discussed.

Procedural law in the new Unified Patent Court (UPC)

The rules of procedure of the Unified Patent Court are similar to the basic structures and procedures of German court proceedings. However, there are special features in the UPC which should be taken care of:

Thus, it is clear that while the patent landscape and litigation in Europe will be made more complex by the new European Unitary Patent and the new Unified Patent Court, these instruments effectively open up additional means and ways of a centralized, effective and relatively inexpensive system for obtaining and enforcing rights. However, achieving the strategic goals will require more than ever good preparation and attention to the peculiarities and tight time regime in the new litigation law.

Further to Part 2: (II) Strategic Considerations of using the new EU Court, or Opting out

Further to Part 3: (III) Comparison of Opposition Proceedings at the EPO and Nullity Proceedings at the UPC

Years of planning finally become reality: The official starting signal has now been given! Germany ratified the Agreement on a Unified Patent Court (UPC) on February 17, 2023.

This means that the final requirements for the entry into force of the Agreement and thus for the start of the Unified Patent Court on June 1, 2023 have been met. As previously reported, the testing phase for the Unified Patent Court’s file management and communication software is already underway, and from March 1, 2023 the sunrise period for filing any opt-out requests will begin.

For more information, please visit: https://www.bmj.de/SharedDocs/Pressemitteilungen/DE/2023/0217_Einheitliches_Patentgericht.html